Despite widespread knowledge of food safety protocols, consumers and food handlers frequently engage in behaviors that increase the risk of foodborne illness. Research reveals this disconnect stems from psychological, social, and systemic factors that override rational safety judgments.

Cognitive Biases and Knowledge Gaps

Many individuals underestimate personal susceptibility to foodborne pathogens due to optimism bias, the belief that “bad outcomes happen to others, not me.” This manifests in ignoring expiration dates, cross-contamination risks, or inadequate cooking temperatures. Additionally, consumers often lack specific safety knowledge, such as the “danger zone” (41°F to135°F) where bacteria multiply rapidly, or the need to reheat leftovers to 165°F within two hours. Industry workers may bypass protocols like handwashing or equipment sanitization when pressured by efficiency demands.

Emotional and Stress Triggers

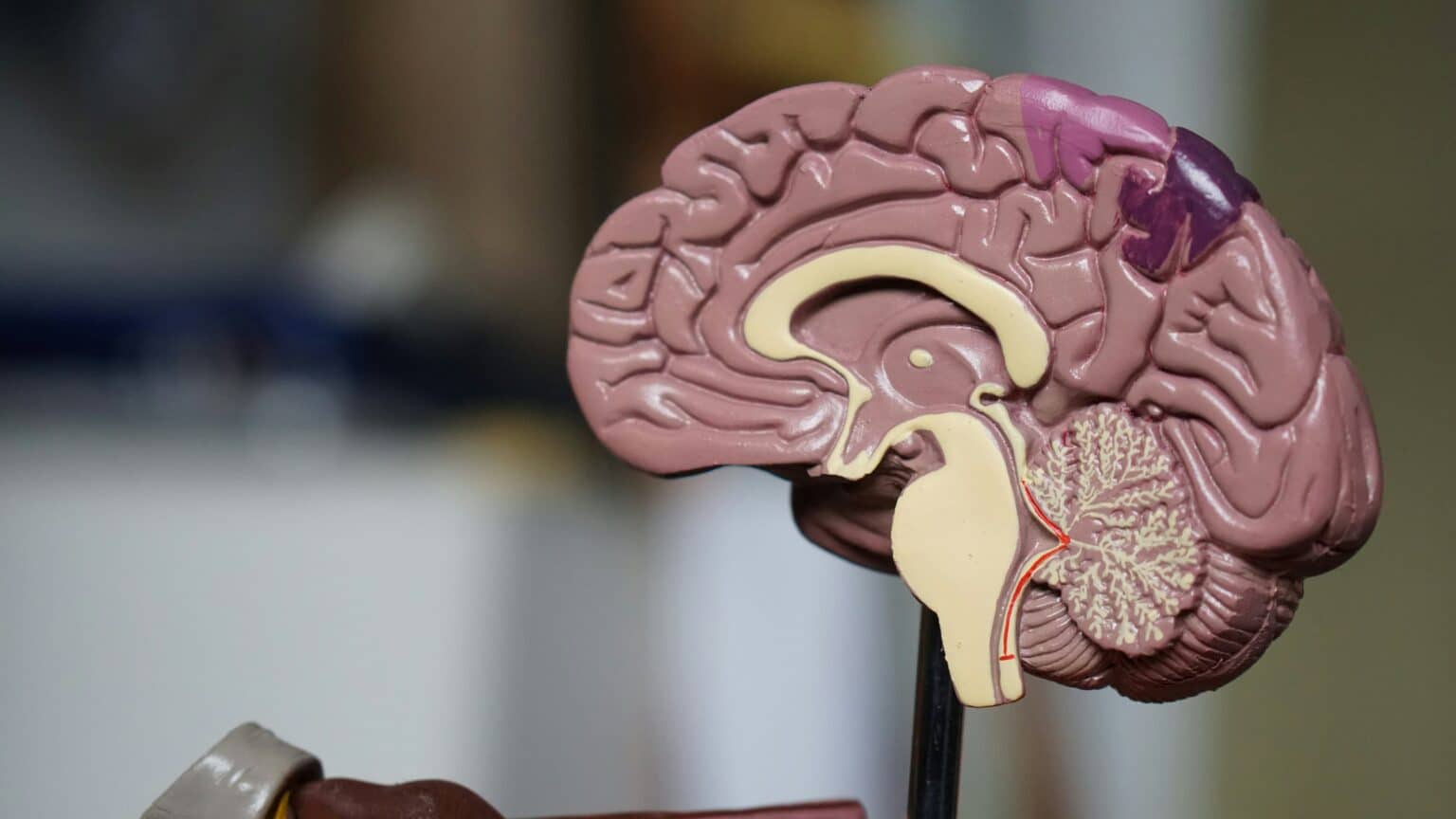

Stress directly impacts food-related risk-taking. During high-anxiety periods, approximately 40% of individuals increase consumption of hyperpalatable “comfort foods” (high-fat, high-sugar items), often prioritizing immediate emotional relief over safety considerations like proper storage or sourcing. This is neurologically reinforced: stress alters the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and mesolimbic dopamine pathways, amplifying cravings for rewarding, but potentially hazardous, foods. Over time, chronic stress may diminish vigilance toward safe handling practices.

Social and Environmental Pressures

Risky eating behaviors are socially contagious. Shared indulgence in undercooked foods or unpasteurized products can strengthen interpersonal bonds, as joint “rule-breaking” generates camaraderie. One study noted that individuals consume riskier foods more frequently with close friends than acquaintances, suggesting social intimacy overrides caution. Workplace cultures also contribute; employees may skip safety steps like glove changes to avoid slowing service during peak hours, while managers facing profit pressures might source cheaper, non-compliant ingredients.

Systemic Vulnerabilities

The “last mile” of food handling, where delivery, storage, or final preparation occurs, is particularly prone to lapses. Time pressures, inadequate monitoring, and decentralized decision-making allow errors like improper cooling or temperature abuse to go unchecked. This is compounded when organizations prioritize efficiency over documented safety audits, creating environments where shortcuts become normalized.

Understanding these psychological drivers highlights the need for targeted interventions: simplified safety messaging, stress-management resources, and accountability systems that address human behavior alongside regulatory standards.