Campylobacter Infection: Where It Comes From and Why It’s One of the Most Common Foodborne Illnesses

Campylobacter is one of the leading causes of foodborne illness, yet it remains less recognized than other well-known pathogens. Its ability to cause widespread illness stems not from dramatic outbreaks or obvious food spoilage, but from its subtle presence in everyday food environments. Campylobacter infections often feel ordinary at first, presenting as gastrointestinal discomfort that many people dismiss as a routine stomach bug. This quiet nature allows the bacterium to spread and persist with little attention.

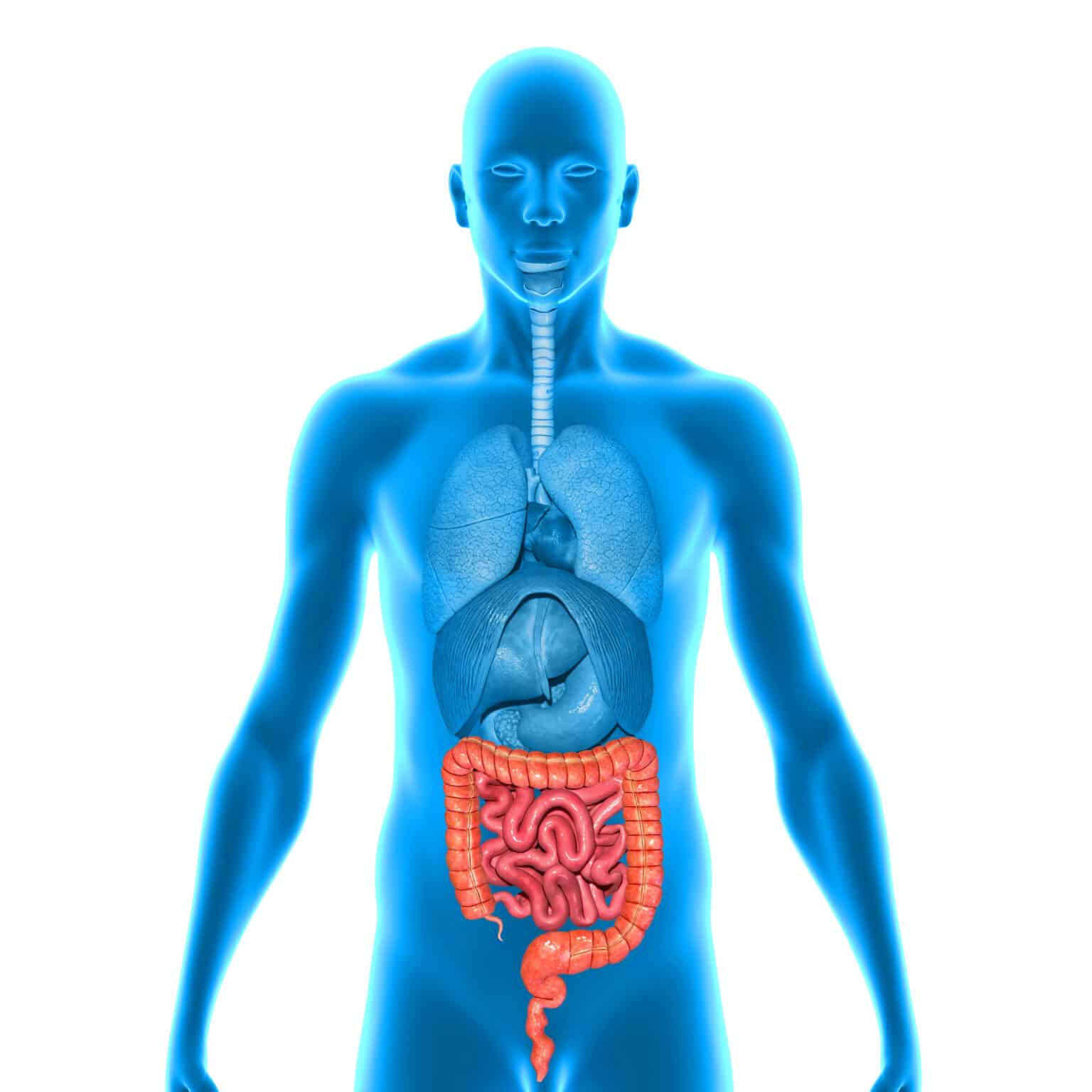

The bacterium is commonly found in the intestines of animals, particularly poultry, where it exists without causing illness. Because it does not visibly affect the animals that carry it, Campylobacter can enter the food supply unnoticed. During processing, raw poultry can become contaminated, and once present, the bacteria are difficult to eliminate without proper cooking and handling. Unlike spoilage organisms, Campylobacter does not change the smell, taste, or appearance of food, making contamination impossible to detect without laboratory testing.

One of the defining features of Campylobacter infection is its incubation period. Symptoms usually develop several days after exposure rather than immediately. This delay creates confusion for both individuals and healthcare providers, as the meal responsible for the infection may not seem relevant by the time illness begins. People often associate symptoms with the most recent food they consumed, which may not be the true source of exposure.

The symptoms of Campylobacter infection typically include diarrhea, abdominal cramping, fever, nausea, and fatigue. In some cases, diarrhea may be severe or persistent, leading to dehydration. Because these symptoms closely resemble viral gastroenteritis, many infections are misdiagnosed or go undiagnosed altogether. When symptoms improve without medical intervention, individuals rarely seek care, further contributing to underreporting.

Foodborne transmission most commonly occurs through undercooked poultry, unpasteurized dairy products, and contaminated water. Poultry is particularly significant because Campylobacter is frequently present on raw chicken, even when the product appears clean and properly packaged. During preparation, bacteria can easily spread from raw meat to hands, cutting boards, countertops, utensils, and nearby foods. Once cross-contamination occurs, ready-to-eat foods can become vehicles for infection without ever being cooked.

Improper cooking remains a critical factor. Poultry that appears fully cooked on the outside may still harbor live bacteria internally if it has not reached a safe internal temperature. Relying on color, texture, or cooking time alone increases the risk of serving contaminated food. Campylobacter is sensitive to heat, but only when food is cooked thoroughly and evenly.

Cross-contamination is one of the most common and underestimated pathways for infection. A cutting board used for raw poultry may later be used for vegetables or bread. A sponge or cloth used to wipe up raw meat juices can spread bacteria across kitchen surfaces. Because Campylobacter is invisible and odorless, these transfers often go unnoticed until illness develops days later.

Water can also play a role in Campylobacter transmission. Untreated or improperly treated water used for drinking, washing produce, or cleaning food preparation surfaces can introduce the bacterium into kitchens. While waterborne exposure is less common in developed settings, it remains a risk when sanitation systems fail or when individuals consume water from unsafe sources.

The severity of Campylobacter infection varies widely. Some individuals experience mild illness that resolves within a few days, while others develop severe symptoms that last longer. Dehydration, prolonged diarrhea, and systemic symptoms can occur, particularly in vulnerable populations. Young children, older adults, and individuals with weakened immune systems are more likely to experience complications, though healthy individuals are not immune to severe illness.

Treatment for Campylobacter infection is generally supportive, focusing on hydration and rest. Antibiotics are reserved for severe cases or individuals at higher risk of complications. Because many infections resolve without medical treatment, laboratory confirmation is uncommon, allowing Campylobacter to remain underrecognized despite its prevalence.

Several misconceptions contribute to ongoing exposure. Many people believe that rinsing raw poultry reduces risk, when in reality it spreads bacteria through splashing. Others assume that food must smell or look spoiled to be unsafe, overlooking the fact that Campylobacter contamination provides no visible warning signs.

The persistence of Campylobacter highlights an important truth about food poisoning. Illness does not require dramatic failures or extreme negligence. Small, routine handling errors are often enough. As long as poultry and other high-risk foods remain staples of everyday diets, Campylobacter will continue to cause illness unless food safety practices are applied consistently.

Understanding where Campylobacter comes from and how it spreads clarifies why prevention depends on attention to everyday habits. Proper cooking, careful separation of raw and ready-to-eat foods, and thorough cleaning of surfaces remain the most effective defenses against a bacterium that thrives on invisibility.