When most people think of food poisoning, they imagine an unpleasant few days of nausea, vomiting, and recovery. But for some, a single contaminated bite can become a matter of life or death. Among all foodborne pathogens, few are as insidious—or as deadly—as Listeria monocytogenes.

Over the past decade, Listeria outbreaks have repeatedly made headlines for contaminating products that seemed harmless: deli meats, soft cheeses, lettuce, cantaloupe, ice cream, even hummus. Behind each recall lies a pathogen capable of surviving where others die, striking hardest at the most vulnerable populations and leaving a wake of hospitalizations, miscarriages, and fatalities.

What Is Listeria?

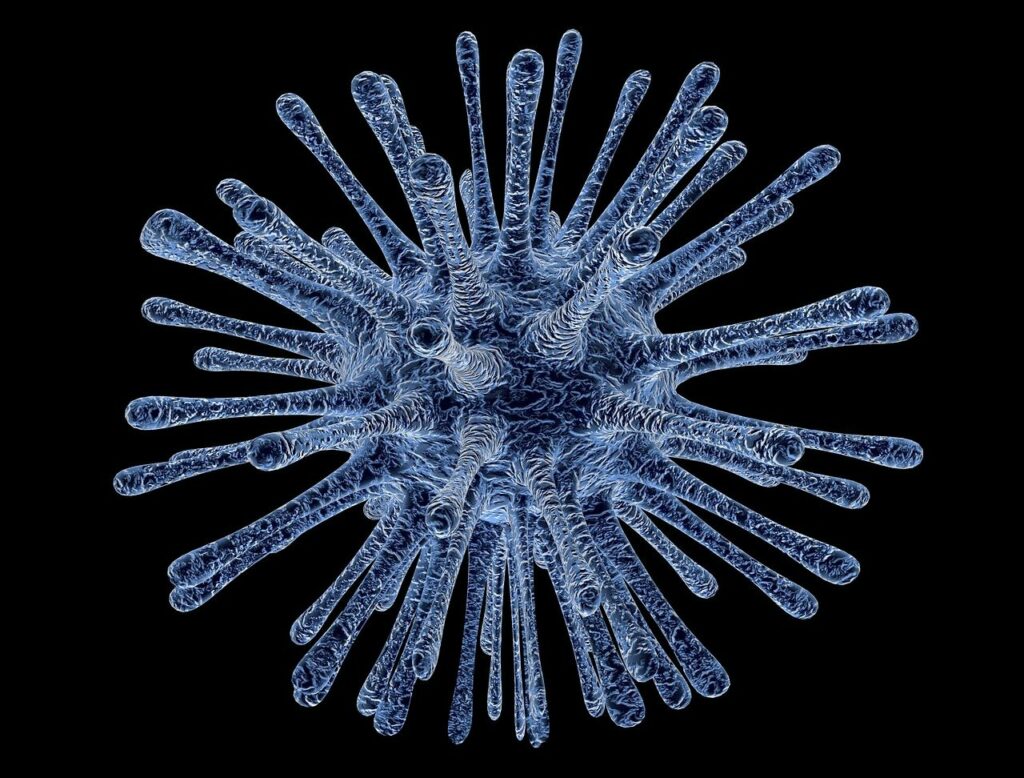

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive bacterium found in soil, water, decaying vegetation, and animal feces. Unlike most bacteria that cause foodborne illness, Listeria has an extraordinary ability to thrive and multiply in cold environments, including refrigerators. This unique characteristic allows it to quietly contaminate ready-to-eat foods long after production, storage, or distribution.

Once ingested, the bacteria can invade the intestinal lining, spread through the bloodstream, and cross into the central nervous system or placenta. The resulting infection, listeriosis, is particularly severe, often requiring hospitalization and long-term treatment.

How Listeria Spreads in Food

Listeria contamination can occur at any point in the food-production process—from farm to fork. It has been found on conveyor belts, cutting machines, storage bins, and even within facility drains. Because it can resist freezing, drying, and certain sanitizers, once it gains a foothold in a food-processing environment, eradication can be extremely difficult.

Some of the most commonly contaminated foods include:

- Deli meats and hot dogs, especially when eaten without reheating

- Soft cheeses such as brie, camembert, queso fresco, and feta

- Pre-packaged salads and leafy greens

- Smoked seafood

- Unpasteurized dairy products

- Ready-to-eat meals and sandwiches

What makes Listeria so dangerous is that even low levels of contamination can be infectious—especially for high-risk groups.

Symptoms and High-Risk Groups

The incubation period for listeriosis ranges from a few days to up to 70 days after exposure, making it one of the most difficult foodborne illnesses to trace. Early symptoms often resemble mild flu: fever, fatigue, muscle aches, or gastrointestinal upset. But once the bacteria spread beyond the intestines, the consequences can escalate rapidly.

In severe cases, Listeria can cause:

- Sepsis (bloodstream infection)

- Meningitis (infection of the brain or spinal cord membranes)

- Pneumonia

- Endocarditis (heart infection)

Certain populations face especially grave risks:

- Pregnant women: Listeria can cross the placenta, leading to miscarriage, stillbirth, or severe neonatal infection.

- Newborns: Exposure during birth or via breast milk can result in life-threatening sepsis or meningitis.

- Elderly adults and immunocompromised individuals (such as cancer patients, transplant recipients, or those with HIV/AIDS) are also highly susceptible.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1,600 people in the U.S. become ill from Listeria each year, and roughly one in five of those infections is fatal.

Why Listeria Is So Hard to Control

Most foodborne pathogens—like Salmonella or E. coli—die off in cold temperatures. Listeria, however, can survive and multiply at refrigerator temperatures (as low as 34°F). It can also form biofilms, sticky bacterial communities that adhere to metal, plastic, or glass surfaces, making them resistant to cleaning agents.

This resilience explains why Listeria continues to appear in ready-to-eat and refrigerated foods, even after processing plants undergo sanitation procedures. Once it enters a facility, it can linger for months or years.

Furthermore, because Listeria infections can take weeks to manifest, outbreaks often remain hidden until several people become seriously ill—by which time contaminated food may have already been consumed or distributed nationwide.

Major Listeria Outbreaks in Recent History

Some of the most devastating foodborne outbreaks in the U.S. have been caused by Listeria:

- 2011: Jensen Farms Cantaloupe Outbreak – The deadliest U.S. foodborne outbreak in nearly a century, killing 33 people, causing one miscarriage, and sickening over 145 people nationwide. The contamination stemmed from unsanitary equipment and poor cleaning protocols.

- 2015: Blue Bell Ice Cream Recall – A multistate outbreak linked to contaminated production lines at an ice cream facility led to 10 hospitalizations and 3 deaths.

- 2021–2024: Multiple Deli Meat and Cheese Outbreaks – Dozens of hospitalizations and fatalities occurred after Listeria was found in deli counters and soft cheese products, many sold nationwide.

Each outbreak revealed the same pattern: environmental contamination, inadequate temperature control, and insufficient monitoring within processing environments.

Preventing Listeria Contamination

While Listeria poses unique challenges, prevention is possible through rigorous food-safety practices. For consumers, the CDC recommends:

- Heating deli meats and hot dogs until steaming hot before eating.

- Avoiding unpasteurized dairy products and soft cheeses unless labeled as made with pasteurized milk.

- Keeping refrigerators at or below 40°F (4°C) and cleaning them regularly.

- Separating raw and cooked foods to avoid cross-contamination.

- Following “use-by” dates carefully on all ready-to-eat items.

For manufacturers and restaurants, strict environmental monitoring, surface sanitation, and employee hygiene are essential. Continuous microbial testing and immediate corrective action upon positive detection are the cornerstones of prevention.

The Legal and Public Health Implications

Because Listeria contamination is often traced to systemic negligence—such as inadequate facility sanitation or failure to test products—victims of listeriosis have legal grounds to pursue compensation.

Outbreak investigations typically involve coordination between the CDC, FDA, and USDA, with genetic sequencing identifying links between patient samples and contaminated foods. Once a source is confirmed, civil litigation often follows to hold manufacturers accountable for negligence.

Victims who contract severe infections, suffer pregnancy loss, or lose loved ones can seek damages for medical costs, pain and suffering, lost income, and wrongful death.

Certain national food safety law firms have represented hundreds of victims in high-profile Listeria outbreaks, helping families obtain justice while advocating for stricter safety standards across the food industry. By pursuing these cases, firms not only secure compensation but also pressure companies to reform unsafe practices—protecting future consumers.

Why Listeria Still Matters

Listeria may not cause the largest number of infections, but it is among the most lethal foodborne pathogens known to science. Its ability to survive in cold, its resistance to disinfectants, and its predilection for ready-to-eat foods make it a persistent threat to public health.

In a world where convenience often trumps caution, the story of Listeria reminds us that vigilance saves lives. Food manufacturers must maintain rigorous control, regulators must enforce accountability, and consumers must stay informed. Each plays a role in breaking the chain of contamination that allows deadly bacteria to reach the dinner table.

Ultimately, the fight against Listeria is not just about preventing illness—it’s about protecting the integrity of the entire food system.